Pythonic Prose

Creating prose that follows the rules to make your life easier

A couple of weeks ago, I talked about certain programming frameworks and languages being good at particular things and how that concept can be applied to selecting a POV. But what I didn't talk about is the programming conventions, or the guidelines that you follow, which helps those programming languages do what they do best. Both programming and writing have conventions that simply make it easier to accomplish certain tasks (in the case of programming) or tell certain stories (in the case of writing).

In programming, these guidelines or conventions have a side benefit of making it easier for other people to read your code, easier for you to debug, and easier to make the program do what it is designed to do. The concept of leaning into these decisions can also be referred to as idiomatic coding or idiomatic programming, and can be as simple as using camelCase or snake_case formats for the names of your functions, or as complicated as requiring a certain file/folder structure before it will allow you to package and publish your code.1

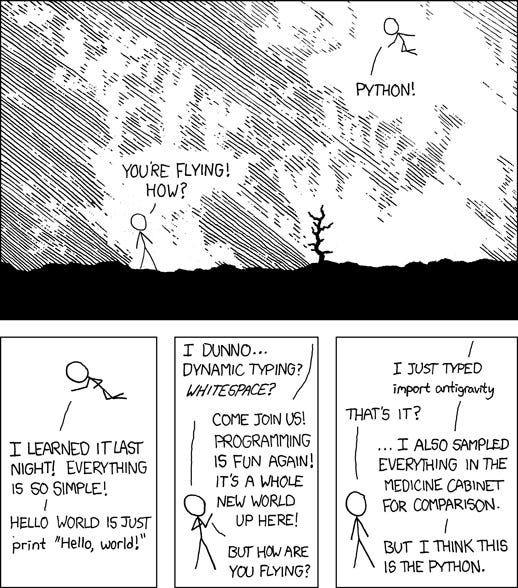

There are many phrases to describe idiomatic code (like Haskellian or Rubyish or Java-esque) but the one that rolls off the tongue best, in my opinion, is Pythonic.

Python is frequently suggested as Baby's First Programming Language: it's simple and fairly straightforward to learn. But because it’s so simple and flexible, idiomatic Python doesn't just mean writing Python code that follows standards and conventions. It's a larger philosophical question about using the language the way it is meant to be used.

I could give examples, but at this point we've been talking about programming for far too long and it's time to talk about what exactly I mean by Pythonic Prose.

Genre is a trap...or is it?

It is a common conceit that adhering to limits can actually be quite freeing for a writer, but let's talk about how limits specifically relate to genre writing. If you are writing within a particular genre, you have specific expectations and conventions you have to keep to. One of the first that comes to mind is that a romance will always end in a happy ending. If it doesn't, you've got a problem.2

Writing in a way that matches the genre expectations is a way of making your prose Pythonic; you are keeping to those expectations so everybody knows what your story is supposed to do, how it's supposed to work. This can be really useful when you're sharing your work with other people. Those who are familiar with the trappings of a genre can help you understand whether you are meeting those expectations or not, and can even provide feedback to make it easier for you to adhere to the conventions of a genre.

Sharing this post also adheres to the conventions of the genre of Substack post. Trust me. It’s true.

Much of this might not apply to literary writing, which has fewer conventions, but if you're thinking from a perspective of "how do I get this story on the page?", go back to your requirements. What story are you trying to tell? And what genre, point-of-view, tense, helps you tell that story the easiest way?

For example, what genre tells a love story best? Or, perhaps not best, but most easily, that lends itself to the craft of describing a love story? Probably romance, right?

The same could be said for mystery or horror or fantasy. The conventions of these genres have been honed by author after author after author to come to a fine set of tropes, characteristics, and scenes that make those genres lends themselves towards a particular type of story. It helps the reader because they know what to expect when they pick up a book in that genre (a happy ending for a romance) but it helps a writer too, because they know what scenes, characters, and problems readers are expecting (they must write a happy ending).

Write What Your Character Knows

For this next aspect of Pythonic prose, let’s explore a hypothetical: if your character is a car mechanic, how do you think she is going to see the world? Even if she is the most well-read person in the world, who studies philosophy and metaphysics in her spare time, who loves to go see Shakespeare and opera and so on, what metaphor do you think she is going to find when she reaches for one at the end of the day? Do you think it'll be a Shakespearean sonnet or a reference to Puccini or Socrates?

Or do you think it'll have something to do with brake pads and windshield wiper fluid and bad alternators?3

Please leave a comment to tell me what I got wrong about cars.

This is the second aspect of Pythonic Prose: write from your character's perspective. Lean into what they know best, what they see and think about and work with each day, and use that as the basis for the way that they describe and interact with the world.

I am not saying your characters only have to think in terms of what their job is or where they grew up or what their family did. But those are useful starting points, and useful to help build character in a subtle way. The choices you make in metaphor, comparison, and comprehension give you a basis to lean into so you can start to really build an interesting perspective.

Maybe a mechanic is more interested in the way certain things fit together when she takes them apart. Maybe a gardener is more interested in nourishing and growing the relationships in their life. Maybe a dancer has more in common with the way a physician sees the world than an abstract painter, because the dancer is interested in the movement of muscles whereas an abstract painter is fascinated by the glow coming from the oil stains on the far side of a puddle.

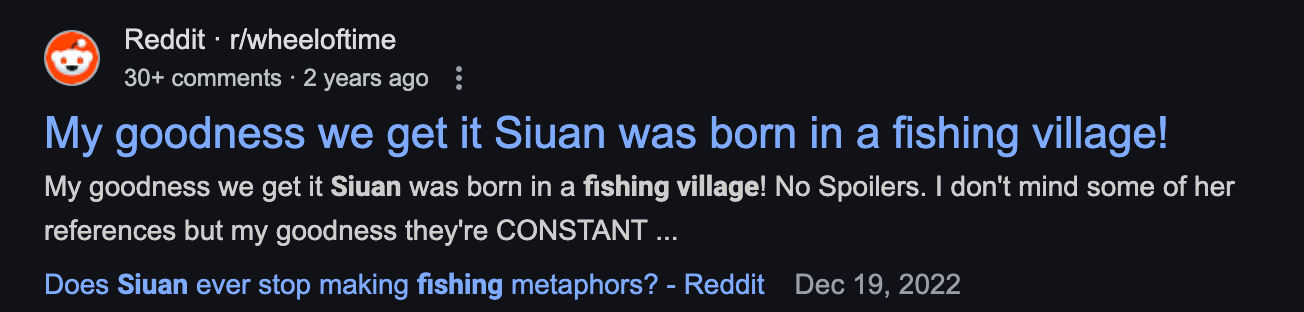

One of the best examples of using a character’s history to provide perspective and color to the way they see the world is from the Wheel of Time. One of the characters in that series grew up in a fishing village and, as a result, she uses references to fishing as the basis for metaphors and comparison.

It’s how she sees the world, it is probably how the world was explained to her, so it makes sense that this is how she would explain things to other characters.

Now, there is such a thing as overdoing it, or over emphasizing a person’s backstory. This character from Wheel of Time (Siuan) has almost become a meme in that particular fandom and her constant references to fishing and “silver pike” are a common complaint amongst new readers.

But using where a person comes from as a reference point for their world view is a pretty good starting point for a character.

Choose the way you write

I have a love-hate relationship with Brandon Sanderson, but I will admit that he knows a thing or two about selling books. In one of his many YouTube videos (I can’t remember which), he told a story about an author friend of his who'd recently had a book come out to limited success.

As he was talking to his friend, who was complaining about the lack of yeast in his sales numbers, Brandon admitted that he had not even read his friends book. He'd gotten about halfway through and gotten bored because it seemed like a common, standard fantasy book.

"But that was the point!" his friend shouted. Apparently, about halfway through the book, he'd subverted the tropes, writing a book that in fact pointed out the flaws with the way those tropes are hypocritical within the genre.

"That's exactly the problem," Brandon said. The readers who are looking for a subversion of that trope aren't going to slog through the first half of a (seemingly) common, standard fantasy book. And the readers who want a common and standard fantasy book are going to give up when they see their beloved expectations being subverted.

You can always choose not to write Pythonic Prose, to subvert the expectations of the genre you're working in, to choose metaphors and similes and descriptions that do not match up with the characters you are writing. But make it a choice, not a subliminal decision, and you'd better be a really, really gifted writer because a writer who is truly gifted doesn't have to care about any of the rules.

After all, if you're going to swim against the current, at least have proper technique in your stroke.

Looking at you, Python.

Not to mention a bunch of angry readers banging on your door, and not in the fun way.

This is where you find out I know literally nothing about cars.

I wrote a lot of computer code during my professional career and I subscribed to the keep it clean and simple camp. I’d rather write 10 lines of code that were simple, clean, and obvious vs 3 lines of code that were obtuse and clever. While either method will work, keeping it simple is the easiest way to maintain the program. I’ve had too many experiences over the years where even with simple code I had a difficult time figuring out what the heck I did when I had to update a program a year after I wrote it and had long forgotten the details of the project.

I write military political Technothrillers so genre fiction. Like all genres there’s expectations. My heroes are smart, tough, brave, and generally act decently. My villains come to a bad ending at the hands of my hero by the last chapter. I try to be very clear early on who is who in the book, what they are after, and whose story it is. I get really frustrated when I read novels and these things aren’t clear. Pythonic writing definitely resonates with me.

My daughter was an early alpha reader of my current book and it felt great when she said, “Dad, after the first chapter I knew what kind of story this was going to be, who the protagonist is, and that I like these kinds of stories.” Great feedback telling me I was headed in the right direction.

ZK, thanks for sharing this insight on approaching writing.