Storytelling Lessons from Programming: Editing via Scrum

Break Your Tasks Down into Small Pieces

Congratulations! You’ve finished writing your first draft and put it aside for three months. Now, you’re looking at it again and wow! It’s not as bad as you thought, but it also has a lot of problems and looking at all of them is really overwhelming. How do you organize all of them? How do you break them down into small pieces?

Well, if you’re like me, you use Scrum techniques that you learned from your day job as a software engineer.

Scrum is way of doing iterative development. In other words, making small changes that work individually, rather than trying to do everything at once.

But how do you figure out what to fix? By gathering your requirements, of course!

Requirements Gathering and Spikes

In programming, requirements gathering falls into two categories: engineer determined requirements and user requirements. In writing, you actually have the same thing: writer determined requirements and reader requirements. Writer determined requirements are the items you identified yourself that need to be fixed as a result of a re-read or exercises, like the Outlining one I talked about in my blogs here and here. The need and want of the character not matching up, for example, or the beats of your story not following logically.

Reader requirements are those things that early readers identified in your story. “This scene seems weird,” for example, or “I don’t understand why x did y.” If you’re lucky, the problems you’ve already identified line up with the ones the readers said, but they don’t always.

Best case, everyone tells you the same thing, you’ve already identified it yourself, and you know how to fix it. Worse case, everyone tells you some thing contradictory, you had no idea, and you have no idea how to fix it.

Dealing with the best case is obvious; you already know what you need to fix.

So how do you deal with worst case scenario?

First, let’s deal with contradictory reactions. The best thing to do in this scenario is listen to everyone without directly taking anyone’s advice. If everyone says a particular scene doesn’t work, but they all have different ideas on why, then there is probably a problem with that scene.

But how to fix it is up to you.

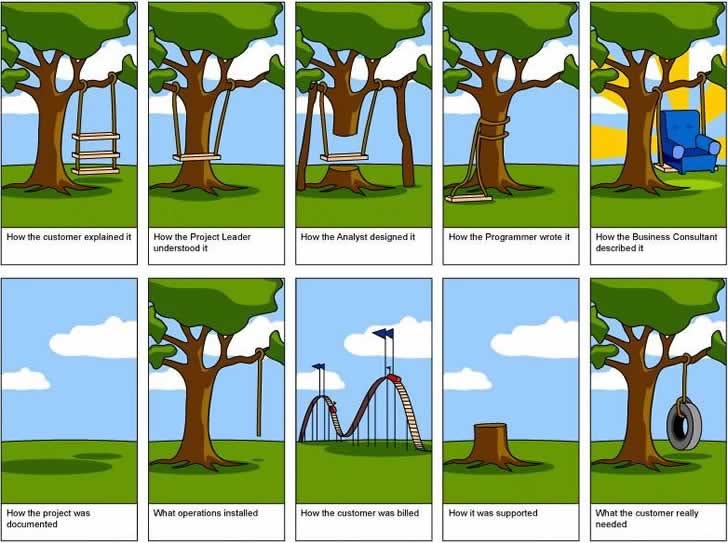

Don’t just immediately take the fixes they provide. Instead, try to determine the underlying problem beneath their statement. This is something you get better at with experience, but if somebody says they want something, try to understand the need behind it. It generally isn’t what they think it is.

For example, if a reader says, “I don’t think the main character would show mercy here. I think they would kill the big bad villain”, that doesn’t necessarily mean, go make the main character kill the villain. It means you haven’t set up the character’s belief in mercy appropriately. If you want that character to be merciful, you need to go back and figure out how to do it.

If half of the people say the scene doesn’t work and the other half say it works fine, listen to why the people who don’t like the scene don’t like it. If what they said strikes a chord for you, then go ahead and fix it. If it doesn’t ring true, then they aren’t the readers for this particular story and that’s okay. Not everyone will like everybody’s work.

The second aspect of the “worst case scenario” is you had no idea the problems were there. This is a terrible feeling, but there’s a reason why you gave your story to these people, right? It’s better to be told by your best friend in your home that your outfit clashes, than to be told by some stranger on the street.

Finally, you have no idea how to fix it. There is a concept within Scrum called a spike. Spikes are meant for figuring out how to do something. In writing, this will take the form of rewriting the same scene multiple times to figure out the best way of doing it, or using writing exercises to figure out how something will work, like a character study.

Scope Creep and Small Changes

After you finish gathering requirements, then you have to start implementation. But you have so much feedback! How do you organize all of it?

The way this is done in Scrum is by breaking them down into categories of changes (called Epics) and then into individual tasks for implementation (called Stories). An example of an Epic for writing could be, “Set up the Villain Earlier” and a Story within that Epic could be “Mention Villain in First Scene”.

You want to break the pieces down into the smallest amount possible so they aren’t overwhelming and the changes feel relatively easy to do, but big enough that they aren’t ridiculous, like changing an individual sentence.

An exercise for writing Epics is to list out the changes that have to happen by referring back to your requirements, paring them down, and then listing each one as a single bullet point.

For example:

Set up the Villain Earlier

Change Main Characters Name

Figure out Side-Character’s Personality

Then, refer back to your book and previous exercises to figure out your Stories:

Set up the Villain Earlier

Mention Villain in First Scene

Change Main Characters Name

Chapter One Re-Read and Edit

Figure out Side-Character’s personality

Spike for Character Study

Update Side-Character Introduction (dependent on results of above spike)

Some of these are just going to be “Go through each chapter and fix it” like changing the main character’s name. But, because that change is so large, it’s useful to break it down by individual chapters so it isn’t as overwhelming.

But why not just go through each chapter and make the changes that are required? Or, better yet, make a list focused on each chapter, list out each task that needs to occur within that chapter, and then make all the changes at once?

Using the example earlier, doing that would look something like this:.

Chapter One

Mention Villain in First Scene

Change Main Characters Name

Update Side-Character Introduction

This is a whole bunch more changes than you were doing earlier, and feels a bit overwhelming just to look at, but it’s only the first chapter so you can do it. You take a couple days and make all of these changes at once and then go back and read-through to make sure it all works.

But it doesn’t.

Something about when you changed the main character’s name in the first scene is off, and you can’t really tell why, and it’s interacting weird with when you mention the villain. And then the transition from that scene to the Side-Character introduction isn’t quite working, and you’re not sure why. But because you’ve made all of those edits at the same time, it’s difficult to pick out exactly why these aren’t working. You now have two choices: revert all your changes and make them again, one by one, or rewrite the whole thing, which was the exact thing you were hoping to avoid.

You can probably see now why this is a little problematic. You’re trying to do a lot all at the same time.

Here’s another way you can get yourself into the same situation: you get into the first Story from our first Epic (Mention Villain in First Scene) and say to yourself, “Hey. While I’m in this first chapter, adding in this conversation, I might as well change the Main Character’s name. It’s not that big of a change, and I’m already here. I might as well.”

There’s a term for this: scope creep.

Limit yourselves to exactly what the task is and no more. You want to make your changes as small and easy to identify as possible so it’s easy to figure out what broke everything.

For example, start with changing your main characters name in your first chapter. Read through it, make sure you didn’t miss any name changes, and that it works smoothly. Now, go add the reference to the villain. Okay, does that scene still work? Does it accomplish the goal of establishing the villain and whatever else it was supposed to do? Now, let’s update the introduction for the side character.

This limits the changes that occur so you can be sure each change works in isolation before implementing the next one. In programming, you’d usually have unit tests to make sure you didn’t break anything, but you can’t automate that in writing, so you’ll have to be your own “tester”, making sure that things didn’t break and it all works smoothly.

Scrum can be applied to more than just writing. I’ve heard of people applying it to music, to art, even to their weekly chore lists they generate with their partner. It’s less of a programming specific mindset and more of an organizational tool, allowing you to break things down into small enough pieces that starting isn’t that hard to do.

There’s an old Chinese proverb: “A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.” All Scrum is trying to help you do is make taking that step seem as easy as possible.

I wrote a lot of computer code when I was still working though never used the "scrum" method as I was never part of an IT group in a large company. Having gotten feedback on several novels I've learned a bit about revision. One thing I find really helpful that you mentioned is a revision plan. I break it up between high level issues that are global to the novel and chapter by chapter changes.

Remember that at the end of the day the story belongs to the writer, not a committee of readers no matter how well intentioned. I've found if multiple people mention the same issue then it's probably something I need to deal with. Don't feel beholden to fix anything and everything that was mentioned by a reader. Also, something I learned recently, is to make sure the person giving you feedback is part of your ideal reader group. If the person giving you feedback doesn't normally read that genre, be suspect of any feedback as it's often way off the mark. Another hard lesson is that it's often better to pay for professional editorial help vs. free help from writer friends. I've gotten far more actionable and useful paid feedback that got me further ahead than free feedback from writer friends.

Most importantly, accept all feedback graciously and never take anything personally. Also, it's your story to be told the way you want. Be clear on your vision and don't apologize or feel beholden to anyone but yourself.

This brought back so many memories! I use a scrum-like approach to drafting and revisions. You are right. You can use it for almost any task.